Feb 17, 2020 | News |

Andrea Swiedom Staff Reporter

Last February, Professor of History Anne Marie Wolf sat traumatized before the TV while images flashed across the screen of children, who had just fled the horrors of their homes and crossed the U.S.-Mexico border, sat on bare concrete warehouse floors trapped in chain link cages.

“I was watching T.V. and getting more and more upset about it and I ended up applying that night [to be a volunteer].” Wolf is fluent in Spanish and applied for a volunteer position in El Paso, Texas at the Annunciation House which provides necessities to newly arrived Central American migrants.

The Annunciation House has provided aid to migrants since 1978 and the program has seen a dramatic spike in numbers during the Trump Administration, which has released a series of new border policies in the past three years. Just between Oct. 2018 and April 2019, according to one Washington Post article, the Annunciation House received 50,000 migrants, and projected estimates only continued to rise. As of December, the House said that they take in an average of 100 people per day.

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CPB) saw a total of 101,774 migrants apprehended at points on the Southwest border at the end of 2019, according to their website, as well as 26,681 migrants deemed inadmissible.

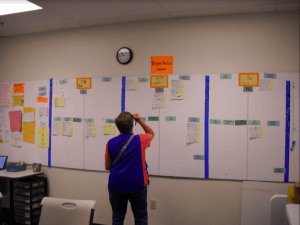

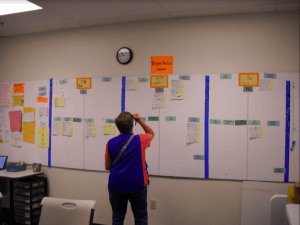

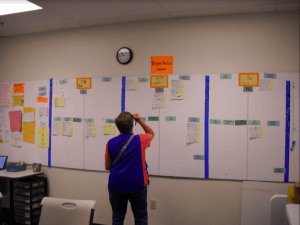

The boards used for coordinating migrants with sponsor families. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Wolf)

In July 2017, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) launched a pilot program in the El Paso, Texas sector authorizing border patrol to separate children from their guardians if they had entered the U.S. illegally.

There were 8,000 separated families, said a report from Amnesty International, by the time this policy was overturned on June 20, 2018. Just a few months prior, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the still current Zero-Tolerance Policy permitting criminal prosecution of anyone crossing the border illegally, regardless of their reasons for making the journey. This was previously a misdemeanor for first-time offenders.

The new policy combined with additional measures from the Trump Administration has resulted in migrants camping out in tent compounds for several months, even a year, as they file asylum paperwork in border towns such as Matamoros, Mexico, on the other side of Brownsville, Texas. These tent compounds pose both a humanitarian and security risk as thousands of people try to maintain a consistent food source, sanitation and ward off human traffickers.

“Nobody would do this, uproot themselves and hang out in a tent on concrete for a year and half,” Wolf said. Those that do cross the border face immediate arrest and are sent to remote detention centers to face prosecution.

“They put these detention centers out in the middle of nowhere because it’s out of sight, out of mind, which makes it difficult because attorneys don’t live in the middle of nowhere,” Wolf said while looking at an aerial photograph on Google of the Stewart Detention Center–an oddly shaped complex in a dense forest 140 miles southwest of Atlanta, GA. “How many immigration attorneys are living out there?”

If migrants are released from these centers, or are fortunate to bypass this step and immediately deemed candidates for asylum by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), they end up at places such as the Annunciation House where volunteers connect them with their sponsor families, provide food, clothing, shelter, transportation money and advice for their next steps.

The average stay for migrants at the House is 36 hours, during which volunteers like Wolf make phone calls to track down sponsor families to support people through the asylum application process. Volunteers also provided what Wolf described as basic hospitality and travel assistance.

Artwork from children from Dr. Wolf’s time working in the Annunciation House. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Wolf)

“For a lot of people it was the first time they had been in an airport or seen an escalator. The El Paso airport is not a big airport, but not speaking the language and everything…we were just helping them navigate,” Wolf said. “There’s a special line for you to go through if you’ve been released through ICE and we would explain that you’re going to be patted down, you’re not going to be arrested.”

When Wolf returned to Farmington, she began providing translation services to pro bono attorneys working with migrants in detention centers.

“Now I am getting deeper into the reasons why these people were leaving. The gang violence is just out of control, people have had their children killed and raped in front of them, they’ve had dead bodies dumped on their doorstep and told, ‘you’re next.’”

Over the phone, Wolf translates intake interviews between attorneys and detainees to gather their reasons for fleeing their countries. She will sit late at night in her office translating court documents and feeling the weight of each person’s life.

“If they get sent back, they have a pretty good chance of being killed,” Wolf said. “The gangs are really organized and they’re organized across national lines. They know if someone has moved and moved in with their sister in another part of the country because they have their affiliates that are looking for that person.”

Each case comes with an emotional toll, but this has not deterred Wolf from continuing to offer her services. “In the summer I will probably be going somewhere to volunteer.”

Feb 17, 2020 | News |

Kathleen Perry Contributing Writer

Students looking for community service opportunities and a touch of college Greek life can look no further than Alpha Phi Omega (APO) which strives to create a community focusing on their main principles: “leadership, friendship, and service.” APO, UMF’s co-ed community service organization, is looking to accept new members into their fraternity, and are on the lookout for students who want to meet new people and serve the campus and Farmington area.

They are a wide-reaching and well respected national organization, that has chapters on many campuses throughout the country including the University of New Hampshire, University of Vermont, and Maine Maritime Academy. APO was established 1991 and has around 500,000 members.

APO Members Kaden Pendleton, Emily Thibodeau, Piper Alexander (Photo courtesy of Madison Vigeant)

APO President Madison Vigeant and APO Vice President Haley Knowlton, both juniors at UMF, agree that the personal connections they have made through the organization go beyond just doing community service, and they feel as though the group has become like a family. To achieve these bonds, once a week the club holds “fellowship,” for the members to spend quality time together through low pressure activities, such as paint nights, movie nights, or, more recently, a snow tubing trip.

The organization also attends conferences out of state. “We’ve gone to Texas, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and at the end of this year we are going to Arizona,” says Elizabeth Leclerc, senior and general member of APO.

One of APO’s most successful events was a bake sale through the United Way in order to benefit victims of the LEAP building explosion in Sept. 2019, taking the life of Captain Michael Bell and affecting the Farmington community. Knowlton said customers would “buy a brownie for fifty cents and hand you a twenty [dollar bill].”

With many community members pitching in to help, the fundraiser made almost $800.

Members of APO join for many reasons. For Vigeant, community service has been a constant in her life for years. “In high school, I was really into community service,” she said. For others, they join to gain skills that will help them in the future.

“APO has helped me to expand my horizons in leadership roles, learn more about community service, and has helped me with organization skills,” says Leclerc.

If students want to get involved with a group that helps out the community, while making lifelong friends, they should attend the first new members meeting on Feb. 10 at 7 p.m. in Ricker Addition 217. While being sworn into the group, each new participant will be paired with a mentor based off of a compatibility test. Throughout each person’s time in the club, they must meet up with their mentor at least once a week in order to keep the connection, and to discuss the community service they are doing, of which APO requires 15 hours per semester.

Vigeant and Knowlton say that if someone is considering joining, they can go to the first meeting and if they don’t like it, they don’t have to stay. “We are very open and friendly and we like meeting new people” says Vigeant.

Feb 17, 2020 | Feature |

Andrea Swiedom Staff Reporter

When Khadija Tawane was seven years old, she fought off her first hyena by waving a stick at the predator while it bit into the back leg of one of her lambs. She didn’t let on to any remembrance of fear, she just laughed and shrugged her shoulders nonchalantly. “Hyenas smell the fear of a human, so we were taught to be brave and strong when we see them.”

Fearlessness was integral to Tawane’s childhood as she herded her family’s livestock- camels, donkeys, goats, sheep and chickens- to water and grazing areas, often walking 15 miles a day in Hagadera, one of three refugee camps in the eastern Kenyan town of Dadaab.

Tawane’s parents left their home in Somalia in 1990 during the early years of the country’s ongoing civil war and walked to what is now the world’s third largest refugee complex. “They fled with their animals, but they had cows and the cows died along the way,” said Tawane.

Her parents still had other livestock when they arrived which provided them with milk, meat and eggs. Tawane’s father began cultivating watermelon and vegetables and the family sold their surplus in exchange for Kenyan shillings that were saved up for the monthly trek into the city center where staples like rice were packed onto the backs of their donkeys.

The livestock provided them with an immediate financial advantage, but the animals were also a part of the family. “I miss my camel,” Tawanee said as she admired a Google picture of a young woman holding the reins to her camel in the Hagadera Camp. Tawane has no pictures of the first twelve years of her life in Kenya, and as she scrolled through internet photos of her home, she went silent and seemed to be lost in the images.

The Tawane name lived on a bulletin board for four years amongst thousands of others until the family of 10 was randomly selected for relocation in Dallas, Texas in 2009.

Khadija Tawane (Photo courtesy of Khadija Tawane)

“When we arrived in Dallas, we didn’t speak English. There were people holding a sign with my father’s name. It was scary, we were all holding hands. We thought we weren’t going to see each other again. When we went into cars, the boys went into a car, and the girls and my mother went into a car.”

Tawane and her siblings felt as though they had experienced the end of the world. “We had this image, like when people leave this place, you were gonna die, you’re done. I don’t know about my parents though.”

Tawane had experienced a dramatic end to the one world she had known, but a new world was just beginning for her: fifth grade in the United States.

“I knew it was a school and I came to learn, but I didn’t feel like I belonged there. And first of all, we grew up wearing long dresses and long hijabs, not t-shirts. And there was a dress code, and sometimes they said no hijabs and my dad had to ask them [to change the dress code].”

Tawane and her siblings would gorge themselves every morning on their mother’s breakfast so that they could avoid the school lunch. “We were afraid there was going to be pork in there,” Tawane said. They were in a completely foreign environment and they couldn’t communicate yet, so it was easier to abstain from the food rather than accidentally consume meat that is considered unclean in Islam.

The family relocated to Lewiston, Maine the next year where Tawane found herself amongst a community of people with similar experiences who even spoke the same Maymay Somali dialect as her. She entered the sixth grade determined to learn English and spent half of the school day in an English Language Learner Program (ELL).

“There were classes just for ELL learners, and everybody spoke different languages, and we were all put in one classroom. But I didn’t want that setting, I wanted to learn the language. I really wanted to be in classrooms where people spoke english with me. I just kept going, and I just remembered the reason we came here was for a better education and a better life.”

While most of Tawane’s peers remained in ELL classes until their sophomore year of high school, Tawane advanced out of the program by eighth grade. She would stay after school everyday and wouldn’t go home until she completed all of her homework.

Tawane attributes her rapid progress in ELL from her Islamic homeschooling taught by her older brother in Hagadera. “Memorization was my key to learning language,” Tawane said, who spent considerable time listening to her brother recite the Qur’an in Arabic and memorizing the verses.

Tawane was also determined to learn about the new society and social norms that she was now a part of, and she giggled telling me she watched a lot of American television. “I also did a lot of sports, cross country, soccer, and softball. But I got a black eye, so only one year of softball, and a year of lacrosse.”

When it came time to think about college, it was never a question of if, but where. “I always wanted to continue my education. That was just my mindset. I didn’t even think oh, people can go in different directions. My mindset was just college. Back in my country, education is the key to success.”

Tawane was accepted to all six colleges that she applied to, but ultimately chose UMF because she already had family here and at the time, she wanted to pursue teaching. She has since changed her major to Psychology.

“I think it’s because the exams that I have to take to become a teacher kind of scare me and also, I realized I don’t want to be in school for the rest of my life,” Tawane said. “And I like to be around children, but maybe if I just had my own office.”

Tawane, now a sophomore, is still happy she chose UMF even though she is no longer pursuing teaching, but the lack of diversity does affect her on a daily basis. “I don’t have a lot of people like me in my classes and I feel like I am standing out. And my professors expect me to speak because they want opinions from different people, and I feel like I am on the spot all the time.”

There are also very basic cultural aspects that Tawane finds herself missing. She showed me Google photos of what the houses look like in Hagadera, camel skin tarps stretched over wooden posts with dried grass mats to cover the sandy ground. They were each one room, large and round shared spaces.

“It’s a different feeling. Here, everybody is put into their own room, but there, you get to talk to your family and you get that bonding. You don’t get that here.”

Nonetheless, Tawane expressed the innate ability to make a home out of any environment.

“Wherever I can find a bed and food, that’s where I call home. And Kenya is home for me.”

Feb 14, 2020 | Sports |

Abbie Hunt Contributing Writer

Senior Katie Leblanc recently qualified for the New England Indoor Track and Field Championship in the 5k. At the beginning of the indoor track season, Leblanc was placed 28th nationally in that race.

Leblanc qualified for the championship at the team’s second meet of the season at the University of Southern Maine (USM). Both Leblanc and Coach Joseph Disalvo, who is no longer coaching at UMF, decided Leblanc’s goal for the season was to qualify for New Englands. The qualifying cut off time for the New England Championship is 18:50, and Leblanc ran her race in 18:46 at the USM meet.

She was close to qualifying at her first race of the season. She went into the race knowing she needed to run 45 seconds per lap (200 meters) to reach her goal. The 5k race is 25 laps around the track. Her initial goal was to qualify at USM, but both she and Disalvo were not expecting her to qualify as early in the season as she did.

At USM, the 5k was her only event. She typically runs the 3k and 5k at meets, but she didn’t want to race both in one day. Leblanc remembered the 5k was the last event of the entire meet. “I was waiting all day,” she said.

Leblanc was focused on her first lap. “When I first started I was really focused because Coach [Disalvo] told me I went out too fast in the race before,” she said. Disalvo was at the 100 meter mark on the track to make sure she was running each lap at the right pace. The race was a mental game. After the first few laps, she was on her own.

Tabitha Lingar, another distance runner on the indoor track team, was there supporting Leblanc during her race. “I was extremely nervous and very anxious for her because she didn’t know if she’d be able to push herself enough that race,” said Lingar. “There were not many other competitors to push her. All of the girls at that meet were slower than her.”

Leblanc didn’t let the lack of competition slow her down. “I didn’t let myself get in my head,” she said.

During the race, she listened to people around for motivation. Around the last seven laps of her race, her vision started going blurry due to a head cold, but she didn’t let that slow her down.

Lingar watched Leblanc’s whole race. “She booked it her last lap,” she said. Leblanc stumbled off the track and Lingar told her that she qualified.

The first thing she remembered Disalvo and Lingar saying was, “you did it.”

Assistant Coach Nickolas Shuckrow also watched Leblanc’s race. “She ran an amazing 5k,” said Shuckrow. “She ran a really tough race where she finished strong.” Although this is Shuckrow’s first season coaching the team, he found Leblanc to be dedicated. “I haven’t known Katie for very long but she is certainly deserving of the opportunity to go run at New Englands,” he said.

At the end of the race she wanted to cry, as she tends to get emotional upon achieving her goals. It was all a blur of high energy for Leblanc the rest of the day, filled with support and excitement from her teammates who were looking forward to seeing Leblanc compete in New Englands.

Leblanc does get nervous for races, but she always tries to remain positive. “Everybody who’s really good will be at that meet and some people are faster than you,” she said. “I get very nervous and I doubt myself which I don’t think is helpful.”

She recently finished the 5k again with a time of 18:35, beating her first qualifying time by nine seconds.

The New England Indoor Track and Field Championship will be held on March 28 and 29 in Middlebury, Vermont.

Feb 14, 2020 | News |

Emily Douin Contributing Writer

UMF’s Multicultural Club is in search of new members as the semester begins to promote diversity and acceptance on campus. The club “embraces people from all over the world, no matter where you come from, you are supported and you are embraced,” president Moninda Marube said with pride.

Currently there are eleven members, three of whom are executive board members. They can be found at their monthly meetings discussing future events, both for the club and also for opportunities for the university to come together. “It embraces people from all over the world, no matter where you come from you are supported and you are embraced,” Marube said.

The club believes that the support that they give one another and also other students of the university, give people a sense of belonging. When new students come from different states and different parts of the world, the club makes the effort to make them feel welcome, accepted and wanted.

The group is in search of new members due to the “desperate need for diversity on this campus.” Cha Cha Jerome said (the club treasurer). “Anyone and everyone should feel welcome here,” Jerome said. They take pride in their ability to set differences aside and be there for one another as a collective unit.

The club has on and off-site events which are available to both members and non-members of the club. Some of these include functions like Pop of Culture Dance, henna art nights and dinners. Off-site events include Rockland trips, conferences, movie viewings, and festivals. The club’s events are not specific to one culture as they make the effort to embrace all of the cultures which are present in the club and that members are interested in learning about.

The club recently attended African Night in Portland which allowed viewers to explore African culture through poetry, food, music and fashion. The Multi-Cultural Club supported one of its own members, Shukri Abdirahman, who performed her poetry. They only a small section of the crowd, with many people from all over the U.S. and Canada in attendance.

They’re planning a trip to the Portland stage in March to see “Native Gardens,” about a mixed racial couple and their journey, followed by a dinner for the entire group.

The club has grown tremendously in the past two years, having more than tripled in size. But that isn’t enough as the club is looking to grow even larger to help spread diversity on campus. “The more people we have in the club, hopefully, we can create more activists, and more meaningful events on campus,” Abdirahman said.

The campus is looking to double their numbers in the upcoming years, which will allow them to have bigger events that will provide the university with more diversity awareness allowing people to feel more accepted and welcome. The club hopes that their events can bring the campus community together and become more accepting of each other.