Mar 13, 2020 | News |

Andrea Swiedom, Staff Reporter

The National Student Exchange (NSE) provides UMF students with the unique opportunity to study at different campuses in the U.S. and surrounding territories, such as Guam, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands and Canada for a semester or full year. Students choose their top three campuses from the list of participating institutions and are accepted based on placement availability.

What makes NSE alluring is the program’s affordability, as Lynne Eustis, Assistant Director of Global Education, explained in an email. “Students pay their normal tuition and fees to UMF, and do not pay tuition to the host school,” she said. “Room and board are paid directly to the host school. Financial aid can be used for this exchange program.”

UMF senior Darby Murnane studied for the Fall 2018 semester at the State Univeristy of New York at Potsdam (SUNY), and was able to apply all of her scholarships and grants towards the exchange tuition. The ability to apply her financial aid towards SUNY was integral to her decision to participate in the NSE program.

She had been considering transferring to another school, but her impressive financial aid package from UMF made her feel obligated to stay. “I started shopping around, and when I heard about the NSE program I thought it was a way to transfer without commitment,” Murnane said.

For senior Zoe Stonetree, NSE was a means to visit a place that has always intrigued her. “I got an email,” Stonetree said excitedly. “The title of the email read, ‘you can go to Alaska.’ I had already been thinking about Alaska, so I took it as a sign, as silly as that sounds.”

Stonetree spent the Fall 2018 semester at the University of Alaska Southeast, in the southeastern capital city of Juneau, Alaska. While there, she took an environmental science course with a lab that included a conference on marine mammalogy, to fulfill a general education requirement. She also took a creative writing course that counted towards her creative writing major, and some endemic courses like backpacking in Alaska.

“We had a bear safety course, learned how to use a compass and what kind of equipment is necessary, and we had a couple of overnight trips,” Stonetree said.

Over the years, Eustis has seen students use this exchange program for a variety of purposes. “Students participate in NSE for many different reasons. . . to take classes not available at UMF, broaden their education perspective, pursue research, field studies, internship opportunities, investigate graduate schools, and make connections in a new job market,” Eustis said.

Ultimately for Stonetree, experiencing all that Alaska had to offer was more important to her than the university, but for Murnane, the courses at SUNY were her main motivators for choosing NSE. “I had discovered that journalism was what I wanted to do,” Murnane said. “They just had more journalistic resources for me to test out.”

While at SUNY, Murnane took courses in magazine writing and mass media, and worked as a staff reporter for the school newspaper. She was very involved with her temporary campus during her time there, participating in swing dancing, mixed martial arts, the school’s radio station as well as working as a lifeguard and swim instructor. Murnane enjoyed SUNY’s vibrant campus life and a change in environment that even included an emphasis on healthy, fresh food.

“There were three places where I could get pasta sauteed to order! Oh my god, the tortellini,” Murnane said, waving her hand in the air. “They didn’t have a third-party food company; they cooked everything in-house. They even had salad greens growing under UV lights in the dining hall!”

Despite Murnane’s positive experience at SUNY and decadent dining, she realized that UMF was where she wanted to be, which is also what junior Megan Scheckells realized after her NSE year.

Scheckells originates from Kansas City, KS, and was attending Emporia State University when she applied to UMF for the 2018-2019 academic year through the NSE program. “I thought, I am just going to do this for a year to test the waters and try out life someplace new,” Scheckells said.

Much like Stonetree’s reason for choosing Alaska, Scheckells chose UMF because she had always felt drawn to Maine. “I feel like a lot of people just have that state that they want to go to, and they don’t have a specific reason why,” Scheckells said.

During Scheckells’ NSE year at UMF, she built unique and important bonds with people, which she attributed to NSE’s requirement that exchange students live on-campus. “I never intended to take the dorm option, but I think they want to create a community, ” Scheckells said. “In the long run, I think it was good.”

Stonetree also attributed the connections she made in Juneau to NSE’s dorm requirement, which inevitably puts students in touch with other NSE exchange students. “I did feel pretty comfortable pretty quickly,” Stonetree said. “There was a big group of NSE people, so it was pretty easy for me to fall into that group.”

While Scheckells spent her first year in Maine, she grew enamored with the close proximity to outdoor activities compared to Kansas, and she went on her first hike to Bald Mountain. “You’re just not surrounded by the woods and mountains [in Kansas] the same way you are here.”

Scheckells was also impressed by the discussion-based English courses offered at UMF, and as her exchange year came to an end, she felt very strongly about staying. “There was a lot to think about just with my family missing me and money-wise, because the flights to and from Kansas are a lot of money,” Scheckells said. “Quite frankly, the biggest reason for me moving to Maine was because I made a lot of genuine connections.”

NSE was also such a positive experience for Stonetree that she considered extending her semester into a year long exchange in Juneau, but was ultimately happy to return to Maine. “I noticed that once I came back from Juneau I was way more into Farmington. I had much more of a desire to be a part of the community,” Stonetree said, pausing to articulate herself. “I have more awareness in general about Maine and what it’s like as a place, because having lived nowhere else I didn’t really know what was particular about living in Maine.”

NSE brought a new perspective to all three students, allowing for a greater appreciation of Maine and UMF. Even so, they all confirmed that they would eventually move on to pursue opportunities in other places. Scheckells wants to go into publishing and plans on moving out of Maine for a job or internship in the future. Stonetree is still exploring her options after graduation. Murnane will be starting graduate school at the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland in the fall of 2020.

If students are interested in participating in NSE for the Fall 2020 semester, Eustis urges students to contact her immediately as the application deadline is April 1. For more information, students can visit the NSE website (https://www.nse.org/) and request an advising session with Eustis (lynne.eustis@maine.edu) through the google form: (https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSdd8QrtU8xlPB1ls58vQWfc1hhjwUZtXuIodoHbJMHZTvIzdQ/viewform).

Feb 29, 2020 | Exclusive |

Andrea Swiedom Staff Reporter

When sophomore Antonio Cortez, 36, brought his wife to his parent’s house for the first time, she thought his brothers were initiating a spontaneous sleepover after dinner as they pulled out pillows and blankets. Cortez had to explain that was just their bed.

“I grew up sleeping on a living room floor,” Cortez said. There with him were his four brothers in a one bedroom apartment in Anaheim, CA.

In hopes of providing a better future for their children, Cortez’s parents crossed the border from Southern Mexico. “They wanted their American-born children to go to college,” Cortez said.

In 2002, Cortez enrolled in a vocational program in Orange County, CA where he earned an associates degree in mechanical engineering while working full-time as a cement mason. But he always had military service in mind as a back-up plan. By 2004, it became his best option. “Eventually I just got to the point where, we were struggling, we needed health care. It was really the lure of the financial assistance.”

Cortez’s wife was struggling with health problems and the hospital bills were continuously draining their savings. “I made up to 30 bucks an hour, but it seemed like every time we visited the hospital it was a couple thousand dollars,” Cortez said.

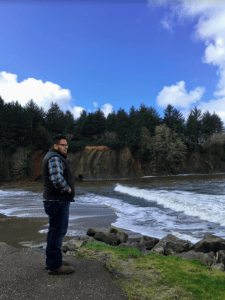

Antonio Cortez (Photo Courtesy of Antonio Cortez)

To cover the costs of education and healthcare, Cortez worked 60 hour weeks and saw the physical effects that decades of masonry had on those around him. “I saw a guy doing it for 20 years and he was calloused and sunburnt,” Cortez said, scrunching his fingers. “I thought, I don’t know if I want to do this for the rest of my life.”

Cortez’s first step towards military service was complete happenstance. He was running errands with his father one afternoon when their car got a flat tire. While waiting for roadside assistance, Cortez found himself staring into the window of a recruitment office. A recruiter came outside and convinced Cortez to apply and take the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) test right then and there.

Within a week of the test, Cortez, determined to pursue the most intense level of training, jumped at a last minute opening for a Ranger Airborne spot and left for Army Ranger school.

“They do SERE training which is survival, evasion, resistance and escape and you go through psychological warfare,” he said. “They lock you in a dog kennel, spray you with a hose. . .it’s just seeing how far you can go before you break. You want to be the guy that doesn’t break, but eventually you do.”

Cortez was deployed in Baghdad, Iraq where he manned an old yacht house-turned army base with 12 other American soldiers and 25 Iraqi police. “It had marble floors, a marble staircase and it was all shot up,” he said. “The water was murky brown. It was half mercury and if you ate the fish in the river, you would get jaundice.”

While in Baghdad, he sustained a severe leg injury from a grenade attack while riding in a truck back to the base. He was wounded by what he described as a molten needle that penetrated the three inches of steel and electrical system of the truck before shattering his knee.

“I couldn’t bend my leg; I thought it was gone. I couldn’t feel most of the left side of my body,” Cortez said while gingerly rubbing the side of his left leg.

After eight years of military service, getting shot in the back and jumping out of airplanes, this was ultimately the injury that led to his medical discharge.

“Most of my military career was like, ‘Hey, you’re alive now. Just get through it to get back to hot dogs and Budweiser,’” Cortez said with a straight face.

St MèreÉglise Drop Zone, Fort Bragg, N.C. (Photo Courtesy of Antonio Cortez)

After his recovery, he spent 30 days in a military out-processing program primarily geared towards retirees and left him with little information as to what benefits and services were available to him as an injured veteran coming straight out of combat.

The lack of information influenced his desire to volunteer with veteran programs to inform others about resources available to them as they transition to civilian life.

“I have spent most of my time since the military trying to figure out how to make up for some crummy things I had to do, not necessarily by choice,” Cortez said.

At UMF, he’s studying rehab management with the ultimate aim to work with veterans dealing with post-combat issues.

Cortez landed in Farmington by happenstance just as he ended up in the military. After leaving the army in 2012, he spent several years soul searching. He worked various jobs in the automotive industry and as a millwright designing and welding custom kitchen suites. Once again, he found himself overworked and burnt out.

With some pension funds and the desire to travel, Cortez, his wife and 12 year old son hit the road in an RV traversing the country three times before ending up at a campsite in Canon, Maine. It only took three months at the seasonal site for the family to realize that Maine was home, and Cortez’s son was ready to attend a public school.

“We love small town life. We just like rural because people want to help you just because they want to help,” Cortez said. “People here are just generally great, and it’s beautiful here.”

He expressed a great appreciation for the UMF campus and the relationships he’s formed with professors due to the open atmosphere and small class sizes.

“Farmington is UMF, and UMF is Farmington. And it’s cool that the public is allowed to use the facilities and the gym,” Cortez said. “It’s really a community.”

Feb 28, 2020 | Feature |

Andrea Swiedom Staff Reporter

Title IX is a federal law that protects individuals at federally-funded institutions like UMF from discrimination including sexual harassment and assault as these impede on a person’s participation in education. When students experience sexual harassment and/or assault on campus, they have the option of reporting their case to mandated reporters who include the majority of faculty, staff, certain students employees, volunteers and peer advocates.

“The only people out of this list who are not mandated reporters are the mental health counselors in the Center for Student Development, the UMF Health Center Staff, and Athletic Trainers when they are working in their Athletic Training capacity,” said Hope Shore, Assistant Director of Student Life & Deputy Title IX Coordinator through an email interview.

When a student reports an incident, the mandated reporter must then inform Shore of the incident.

“I will then reach out to the student to see if they would like to meet,” Shore said. “If the student is interested, I will provide them with information about resources, support, campus policies and procedures and available accommodations.”

Students or anyone concerned with an incident may bypass a mandated reporter by filling out the Title IX Incident Reporting Form online located on MyCampus under the Campus Safety tab or through the UMF Title IX website. This online form allows individuals to file their incident anonymously.

Franklin Hall, Counseling is located on the second floor (Photo courtesy of Andrea Swiedom).

Individuals can also report an incident directly to Shore, which is what a group of students did in Dec. 2018 after encountering several occurrences of sexual harassment from the same individual.

The group of students will remain anonymous for their protection as the Flyer staff is aware of their identities and is confident in the credibility of their stories.

The group created a form for everyone involved to fill out and turn into Shore that described their experiences with this individual. One of the students involved expected the incident to be filed under the group’s name. However, even if a case is recorded with a group, each person’s case is treated as an individual report.

Although students have no obligation to go any further once an incident has been brought to Shore’s attention, one of the members of the group that reported the harassment decided to proceed with the Title IX process. “I can back out at any point, but since I knew others were moving forward, I was going to move forward,” they said.

After the group filed their statement, the student met with Shore one-on-one to continue with the process. “I got this big folder of information and she basically told me that she would make the decision on who she would kind of push my case to next and it ended up going to Christine Wilson,” said the student.

They met with Wilson, the Vice President of Student Affairs, to provide yet another statement that would determine whether or not the case would receive a full investigation. “It felt very official, kind of intimidatingly official,” the student said. “I thought I was just meeting with Christine, but when I got there, there was another woman directly connected with Title IX who was just there for recording.”

The student was allowed to bring a person along for support while giving their official statement. “They were not allowed to say anything, but they were allowed to just be there, which I thought was a really nice thing that you can do,” they said.

The incident was warranted a full investigation at the end of January. They were anxious and afraid while awaiting a verdict as they still had to function in classes, school activities and live on campus around the accused individual.

“I don’t want this to last the entire semester. I just wish they had given me a rough timeline. It’s just, you’ll hear from us when you hear from us,” they said.

Shore’s office also provides students with the option to file a No-Contact order, which prohibits the accused from interacting with the accuser until a verdict is reached. However, the No-Contact order has its limitations.

The student described an interaction they had recently in the Student Center with the individual whom they filed the complaint against, while tabling for a club. “He decided to walk right up to the table to start talking to a person next to me. I asked Hope if this breaks the No-Contact order and she said no. I was having a panic attack and I wasn’t able to do anything about it,” they said.

Whether or not students go through with the Title IX process, there are several support resources available on campus that Shore reviews with students during initial meetings. “[Shore] asked me if I knew what services are available. I kind of knew, but at the same time I didn’t,” the student said. “I still said that I knew because I didn’t want to be there, but at the same time, I know that the counselors in Franklin have a month-long waiting list.”

None of the counselors were available for an interview, but students can visit the counseling services website for more information or visit their office on the second floor of Franklin Hall, which is open Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. The Counseling Center also provides emergency walk-in hours that students may take advantage of at any time.

Shawna Austin, SAPARS Associate Director (Photo Courtesy of Shawna Austin).

There is also a confidential, free drop-in support service available in room 112 in the Student Center every Friday from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. through Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Services (SAPARS). “This is a specific time where an advocate can be accessible to answer questions, be a listening ear, and/or work together with students to engage in awareness raising events and/or other projects,” said Associate Director of SAPARS Shawna Austin in an email interview.

SAPARS isn’t affiliated with UMF, but offers an impressive amount of free and confidential support services, including a 24-hour helpline (1-800-871-7741) to assist anyone affected by sexual harassment and/or assault, support groups, and a Sexual Assault Response Team well-versed in legal procedures that will even accompany individuals to police stations.

Feb 17, 2020 | News |

Andrea Swiedom Staff Reporter

Last February, Professor of History Anne Marie Wolf sat traumatized before the TV while images flashed across the screen of children, who had just fled the horrors of their homes and crossed the U.S.-Mexico border, sat on bare concrete warehouse floors trapped in chain link cages.

“I was watching T.V. and getting more and more upset about it and I ended up applying that night [to be a volunteer].” Wolf is fluent in Spanish and applied for a volunteer position in El Paso, Texas at the Annunciation House which provides necessities to newly arrived Central American migrants.

The Annunciation House has provided aid to migrants since 1978 and the program has seen a dramatic spike in numbers during the Trump Administration, which has released a series of new border policies in the past three years. Just between Oct. 2018 and April 2019, according to one Washington Post article, the Annunciation House received 50,000 migrants, and projected estimates only continued to rise. As of December, the House said that they take in an average of 100 people per day.

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CPB) saw a total of 101,774 migrants apprehended at points on the Southwest border at the end of 2019, according to their website, as well as 26,681 migrants deemed inadmissible.

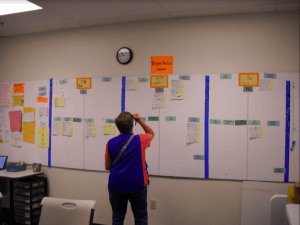

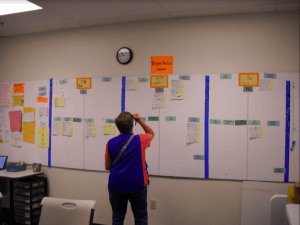

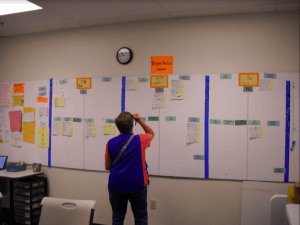

The boards used for coordinating migrants with sponsor families. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Wolf)

In July 2017, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) launched a pilot program in the El Paso, Texas sector authorizing border patrol to separate children from their guardians if they had entered the U.S. illegally.

There were 8,000 separated families, said a report from Amnesty International, by the time this policy was overturned on June 20, 2018. Just a few months prior, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the still current Zero-Tolerance Policy permitting criminal prosecution of anyone crossing the border illegally, regardless of their reasons for making the journey. This was previously a misdemeanor for first-time offenders.

The new policy combined with additional measures from the Trump Administration has resulted in migrants camping out in tent compounds for several months, even a year, as they file asylum paperwork in border towns such as Matamoros, Mexico, on the other side of Brownsville, Texas. These tent compounds pose both a humanitarian and security risk as thousands of people try to maintain a consistent food source, sanitation and ward off human traffickers.

“Nobody would do this, uproot themselves and hang out in a tent on concrete for a year and half,” Wolf said. Those that do cross the border face immediate arrest and are sent to remote detention centers to face prosecution.

“They put these detention centers out in the middle of nowhere because it’s out of sight, out of mind, which makes it difficult because attorneys don’t live in the middle of nowhere,” Wolf said while looking at an aerial photograph on Google of the Stewart Detention Center–an oddly shaped complex in a dense forest 140 miles southwest of Atlanta, GA. “How many immigration attorneys are living out there?”

If migrants are released from these centers, or are fortunate to bypass this step and immediately deemed candidates for asylum by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), they end up at places such as the Annunciation House where volunteers connect them with their sponsor families, provide food, clothing, shelter, transportation money and advice for their next steps.

The average stay for migrants at the House is 36 hours, during which volunteers like Wolf make phone calls to track down sponsor families to support people through the asylum application process. Volunteers also provided what Wolf described as basic hospitality and travel assistance.

Artwork from children from Dr. Wolf’s time working in the Annunciation House. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Wolf)

“For a lot of people it was the first time they had been in an airport or seen an escalator. The El Paso airport is not a big airport, but not speaking the language and everything…we were just helping them navigate,” Wolf said. “There’s a special line for you to go through if you’ve been released through ICE and we would explain that you’re going to be patted down, you’re not going to be arrested.”

When Wolf returned to Farmington, she began providing translation services to pro bono attorneys working with migrants in detention centers.

“Now I am getting deeper into the reasons why these people were leaving. The gang violence is just out of control, people have had their children killed and raped in front of them, they’ve had dead bodies dumped on their doorstep and told, ‘you’re next.’”

Over the phone, Wolf translates intake interviews between attorneys and detainees to gather their reasons for fleeing their countries. She will sit late at night in her office translating court documents and feeling the weight of each person’s life.

“If they get sent back, they have a pretty good chance of being killed,” Wolf said. “The gangs are really organized and they’re organized across national lines. They know if someone has moved and moved in with their sister in another part of the country because they have their affiliates that are looking for that person.”

Each case comes with an emotional toll, but this has not deterred Wolf from continuing to offer her services. “In the summer I will probably be going somewhere to volunteer.”

Feb 17, 2020 | Feature |

Andrea Swiedom Staff Reporter

When Khadija Tawane was seven years old, she fought off her first hyena by waving a stick at the predator while it bit into the back leg of one of her lambs. She didn’t let on to any remembrance of fear, she just laughed and shrugged her shoulders nonchalantly. “Hyenas smell the fear of a human, so we were taught to be brave and strong when we see them.”

Fearlessness was integral to Tawane’s childhood as she herded her family’s livestock- camels, donkeys, goats, sheep and chickens- to water and grazing areas, often walking 15 miles a day in Hagadera, one of three refugee camps in the eastern Kenyan town of Dadaab.

Tawane’s parents left their home in Somalia in 1990 during the early years of the country’s ongoing civil war and walked to what is now the world’s third largest refugee complex. “They fled with their animals, but they had cows and the cows died along the way,” said Tawane.

Her parents still had other livestock when they arrived which provided them with milk, meat and eggs. Tawane’s father began cultivating watermelon and vegetables and the family sold their surplus in exchange for Kenyan shillings that were saved up for the monthly trek into the city center where staples like rice were packed onto the backs of their donkeys.

The livestock provided them with an immediate financial advantage, but the animals were also a part of the family. “I miss my camel,” Tawanee said as she admired a Google picture of a young woman holding the reins to her camel in the Hagadera Camp. Tawane has no pictures of the first twelve years of her life in Kenya, and as she scrolled through internet photos of her home, she went silent and seemed to be lost in the images.

The Tawane name lived on a bulletin board for four years amongst thousands of others until the family of 10 was randomly selected for relocation in Dallas, Texas in 2009.

Khadija Tawane (Photo courtesy of Khadija Tawane)

“When we arrived in Dallas, we didn’t speak English. There were people holding a sign with my father’s name. It was scary, we were all holding hands. We thought we weren’t going to see each other again. When we went into cars, the boys went into a car, and the girls and my mother went into a car.”

Tawane and her siblings felt as though they had experienced the end of the world. “We had this image, like when people leave this place, you were gonna die, you’re done. I don’t know about my parents though.”

Tawane had experienced a dramatic end to the one world she had known, but a new world was just beginning for her: fifth grade in the United States.

“I knew it was a school and I came to learn, but I didn’t feel like I belonged there. And first of all, we grew up wearing long dresses and long hijabs, not t-shirts. And there was a dress code, and sometimes they said no hijabs and my dad had to ask them [to change the dress code].”

Tawane and her siblings would gorge themselves every morning on their mother’s breakfast so that they could avoid the school lunch. “We were afraid there was going to be pork in there,” Tawane said. They were in a completely foreign environment and they couldn’t communicate yet, so it was easier to abstain from the food rather than accidentally consume meat that is considered unclean in Islam.

The family relocated to Lewiston, Maine the next year where Tawane found herself amongst a community of people with similar experiences who even spoke the same Maymay Somali dialect as her. She entered the sixth grade determined to learn English and spent half of the school day in an English Language Learner Program (ELL).

“There were classes just for ELL learners, and everybody spoke different languages, and we were all put in one classroom. But I didn’t want that setting, I wanted to learn the language. I really wanted to be in classrooms where people spoke english with me. I just kept going, and I just remembered the reason we came here was for a better education and a better life.”

While most of Tawane’s peers remained in ELL classes until their sophomore year of high school, Tawane advanced out of the program by eighth grade. She would stay after school everyday and wouldn’t go home until she completed all of her homework.

Tawane attributes her rapid progress in ELL from her Islamic homeschooling taught by her older brother in Hagadera. “Memorization was my key to learning language,” Tawane said, who spent considerable time listening to her brother recite the Qur’an in Arabic and memorizing the verses.

Tawane was also determined to learn about the new society and social norms that she was now a part of, and she giggled telling me she watched a lot of American television. “I also did a lot of sports, cross country, soccer, and softball. But I got a black eye, so only one year of softball, and a year of lacrosse.”

When it came time to think about college, it was never a question of if, but where. “I always wanted to continue my education. That was just my mindset. I didn’t even think oh, people can go in different directions. My mindset was just college. Back in my country, education is the key to success.”

Tawane was accepted to all six colleges that she applied to, but ultimately chose UMF because she already had family here and at the time, she wanted to pursue teaching. She has since changed her major to Psychology.

“I think it’s because the exams that I have to take to become a teacher kind of scare me and also, I realized I don’t want to be in school for the rest of my life,” Tawane said. “And I like to be around children, but maybe if I just had my own office.”

Tawane, now a sophomore, is still happy she chose UMF even though she is no longer pursuing teaching, but the lack of diversity does affect her on a daily basis. “I don’t have a lot of people like me in my classes and I feel like I am standing out. And my professors expect me to speak because they want opinions from different people, and I feel like I am on the spot all the time.”

There are also very basic cultural aspects that Tawane finds herself missing. She showed me Google photos of what the houses look like in Hagadera, camel skin tarps stretched over wooden posts with dried grass mats to cover the sandy ground. They were each one room, large and round shared spaces.

“It’s a different feeling. Here, everybody is put into their own room, but there, you get to talk to your family and you get that bonding. You don’t get that here.”

Nonetheless, Tawane expressed the innate ability to make a home out of any environment.

“Wherever I can find a bed and food, that’s where I call home. And Kenya is home for me.”