Oct 10, 2021 | Exclusive, Feature, News |

By Paige Lusczyk, Contributing Writer.

The University of Maine at Farmington’s Art Gallery will be showcasing installation artist Samantha Jones’ work, “Vital Traces,” until Oct. 28. Last week, Jones spoke about her work at a public reception on Mantor Green.

“Vital Traces” is split up into three different sections, one for each floor of the gallery. Each floor connects to a different feeling of grief.

“There is a joy that comes from the body that the brain can’t handle,” Jones said. The pieces shown in “Vital Traces” and the materials used helped Jones step out of her body and be one with her grief, she said.

“There is no border for me between personal and art,” Jones said. “Our Ego is in the way of our ability to connect to the rest of the world… in the way of saving ourselves.”

The first floor holds many different styles of art ranging from glasswork to jewelry sculptures to digital aluminum prints. Jones likes to call the first floor “Area 51” or “Seance.” The work is all about reaching.

“It’s not human. It’s all types of being,” she said.

With her piece, “Seance with Malka,” Jones admitted to channeling her late grandmother-in-law to help her place each piece of jewelry. The jewelry itself was her grandmother-in-law’s and she felt even more connected to her as she placed each piece.

“She was a walking art piece,” Jones said, “I channeled her.”

One of the more curious display pieces of “Vital Traces” would be the breastmilk soap on the first floor. Jones saw the art as an excretion of the initial process. She connected a child to that process and actually used her own breast milk from nursing her son.

“The art that comes has its own life; it becomes its own. It then gets to teach me,” Jones said. “It is not doing it according to our bidding.”

The second floor is “where the pieces get to reach back.” As you walk up the stairs a beautiful piece is draped along the staircase that is full of life and conversation. The piece, “L’esprit de L’escalier,” was inspired by Diderot, an artist that talked about how we only think of good comebacks when we walk away from the situation. “When the earth starts to speak,” Jones said.

Pieces “Entanglement III” and “Seismic Dreams” are the largest pieces in “Vital Traces.” “Entanglement III” falls differently in every installation. It becomes one with the room.

“Seismic Dreams” was made with no plan. Jones worked in a way with the material so she would not interfere with how it wanted to form. The piece was not titled until Jones opened the folded cloth. “It was telling me what it was,” Jones said.

The third floor is more of a cathartic gesture. It holds only one piece titled “Immanence” which tries to capture the essence of topless churches in Rome. The piece brings a sense of “connecting the architecture to the atmosphere.”

Jones admitted that she sees the “materials [she] works with as living creatures.” Seeing her work as living beings helps the process be more organic for Jones. Although she did admit that “it’s terrifying not knowing where you’re going.”

However, Jones said her art is truly all about the process. Most of the work that she displayed in the gallery was made by trying to avoid a true plan and letting the art speak for itself.

“It is a way into care, it’s a way into reconnecting to things that we have subverted and ignored by trying to make a plan,” Jones said.

Gallery Director, Sarah Maline took the initiative to reach out to Jones. “I had been stalking her work online for a couple of years,” Maline said.

“Vital Traces” was postponed for another year after the initial acceptance because of the pandemic. “The whole show changed after that year. Right? Because you can’t have just…. something that you thought you had, then you’re in a different place, right? You gotta be where you’re at,” Jones said.

Recent UMF Alumna, Samantha Taylor, opened up for Jones in the public reception. Taylor performed by singing and playing songs on a guitar for a half hour.

Feb 28, 2020 | News |

Taylor Burke, Contributing Writer

The VOYAGER: Migrational Narratives exhibit introduces a conversation on migration to the UMF community through various mediums and perspectives. The exhibit, which is free to the public, opened from Jan. 30 to March 6.

Olivia Donaldson and Ann Bartges, curators of the exhibit, recently opened the gallery on a night that included live performances and virtual reality experiences. The exhibit features paintings, collages, photographs, textiles, sculptures, a poem and digital media pieces that viewers can watch and listen to. Each piece explores what it means to migrate and highlights experiences and perspectives on migration.

Donaldson, a French professor, has been researching migration and teaches global studies. She is passionate about migration and interested in the arts. Bartges is the director of the Emery Community Arts Center and a professor of visual arts.

Donaldson and Bartges were friends prior to the project which aided their collaboration. They began conversing about migration over a poem that became part of the exhibit. “In some ways, the poet launched the conversation between Olivia and I a long time ago,” Bartges said, “the poem kind of started the whole idea of the exhibition.” Bartges proposed the idea of the exhibit to Donaldson in her efforts to find ways that Emery could serve the rest of the campus, not just the art department.

The whole project took about a year to complete. “I don’t know if either of us really mapped that out when we started this,” Bartges said laughing with Donaldson. With Bartges’ background in art and Donaldson’s vision for interdisciplinary work, the two complemented each other in the curation process.

Arturo Herrera (left) and David Sanders (right) perform at the opening night for the VOYAGER exhibit. Photo Courtesy of Ann Bartges.

Donaldson and Bartges put out a call for submissions and were presented with a strong pool of pieces. “The works by artists who had experienced migration first hand had so much more depth,” said Bartges. “Those works just tended to have more layers,” she said.

Bartges and Donaldson’s decisions were influenced by their vision for the exhibit and tone they wanted to set. “We really didn’t want the show to become a binary conversation about whether migration is good or bad,” Donaldson said. “We wanted the show to be about connections.”

Bartges found Nayda Cuevas’ piece, “Adios: Puerto Ricans Always in Migration” to capture the tone they wanted for the exhibit. “We wanted to show this really human part of the migration experience,” she said.

This exhibit provides another perspective to understanding migration and its many facets. “We all engage with [migration] in newspaper headlines and in political language,” Bartges said. “But then there’s this other opportunity to engage in these issues through stories and narratives and experiences.”

One of the mediums, included only on opening night, was a virtual reality film called “A Shared Space: Lewiston,” created by documentary filmmaker Daniel Quintanilla and collaborators Shuab Mahat and Hilowle Aden. The film chronicles Mahat and Aden, two friends, who grew up in the Dadaab Refugee Camp in Eastern Kenya and currently live in Lewiston. “It looks at the challenges they each face in raising families in Maine during a time of rising nationalism, closed borders and travel bans,” Quintanilla said in an email.

The virtual reality experience allows viewers to immerse themselves in the content in ways other forms don’t allow for. “[A Shared Space: Lewiston] came out of a need to create content that could help others see and imagine the lives of others,” Quintanilla said.“We saw 360-degree cameras and headsets as a way to create virtual experiences in which we could invite viewers to enter spaces they might not be able to enter on their own.”

The creators of the film wanted to call attention to Maine’s connection with migration and the issues that surround it.“It’s too easy to be passive and think that families separated by ICE, borders, or policies is happening elsewhere,” Quintanilla said. “One of our goals is to highlight Maine’s relationship to global migration.”

This piece, like all of the others in the exhibit, is a way of storytelling and communicating human experiences. “I hope viewers are not only moved by the stories presented,” Quintanilla said in an email. “But can translate that empathy into action of some kind.”

Two of the pieces in the exhibit were created by creative writing professor, Éireann Lorsung. Her first work, “Completely out of Water,” is a collage piece from a series of 15 that she made during her time in Belgium.

Lorsung used this piece to play with English idioms while also channeling her own experience of being foreign. “What happens when you make an idiom literal?” she said. “What’s literally happening is very uncomfortable.” Although the literal meanings of idioms can cause discomfort, the piece was also supposed to evoke some humor due to the differences between the literal and metaphorical meanings of idioms.

Curators Ann Bartges and Olivia Donaldson speak at the opening night of the VOYAGER exhibit. Photo Courtesy of Ann Bartges.

Lorsung’s second piece, “Royaume de lumière x 144,” is part of a series of 144 small paintings that document the land that she lived on and had to leave. There is also a sound bit that goes along with the piece and plays a recording of the sounds from her garden.

When Lorsung left Belgium she lost her sheep and garden, among other things. “There’s no clear way to live through that,” Lorgsung said. “Art is a way that I’m trying to understand all that stuff.”

All the objects in the paintings are drawn from memory in an effort to reclaim what can’t be reclaimed. “Basically all the work I do is really thinking about having been an immigrant and what it meant to leave,” she said.

As an immigrant herself, Lorsung has noticed that migration is generally demeaning despite it being a natural and historical occurrence. “It’s borders and boundaries that are the new thing,” she said. “Human migration is not a new thing.”

Arturo Herrera, who is based in the Detroit area, was the creator of “The National Bird” piece displayed at the exhibit. “The National Bird is an experimental performance series highlighting several migratory animal disguises,” Herrera said in an email. “It builds on the premise that wild creatures can legally cross territorial boundaries anytime and anywhere without checkpoints.”

“The National Bird” gave and still gives Herrera the opportunity to create work that tells his personal story while not being directly about him. The piece is not finished and continues to evolve and grow, much like the subject of migration. “The work provides a different perspective on issues of relevant concern like immigration,” he said.

Herrera attended the opening night of the show and performed using two characters from his series. “[M]y impression was great of the show, as well as how every work in the gallery was speaking with each other,” he said in an email.

Nov 21, 2019 | News |

Zion Hodgkin Contributing Writer

As Maine Gov. Janet Mills recently signed legislation replacing Columbus Day day with Indigenous People’s Day, perspectives on Thanksgiving are changing too. The ethics of the holiday’s very existence as well as the traditions in the celebration of it are now in question.

The first Thanksgiving was celebrated in 1621, and now, nearly 400 years later, it is celebrated in much the same manner. People get together with their loved ones, eat a ton of food, and feel happy about what they’ve achieved- but should we?

“The story goes,” writes one Business Insider article, “friendly local Native Americans swooped in to teach the struggling colonists how to survive in the New World. Then everyone got together to celebrate with a feast in 1621.”

However, the true beginning of Thanksgiving celebrations is believed to start instead in 1637, “owing to the fact Massachusetts colony governor John Winthrop declared a day of thanks-giving,” continues Business Insider, “to celebrate colonial soldiers who had just slaughtered 700 Pequot men, women, and children in what is now Mystic, Connecticut.”

Though the exact specificities and dates of this “First Thanksgiving” event may not be well known, most people, “are more aware that the story isn’t just what was taught in school,” proclaims Austin Kieth, former UMF student. “I just think people are more politically and historically involved. We are more aware of what Indigenous people went through.”

Katrazyna Randall, Associate Professor of Art, speaks about how she feels the holiday isn’t celebrated for the right reasons, but also why she thinks it isn’t celebrated in the right way. “One of the first things that strikes me, is how much it’s become about the idea of the nuclear family. In its origination it was about the harvest and about the community,” says Randall. “We don’t recognize ourselves as part of a community anymore, so that whole concept of it that is something worth celebrating doesn’t really exist anymore, it’s now about getting together with your family to have a dinner.”

Randall continues by thinking about how to shift the way a holiday born from a story of massacre is viewed and celebrated. “I sort of feel like things like Thanksgiving could go away, and that we need to invent new celebrations that celebrate our current civic reality,” Randall says. “I think that we should move more towards community celebrations and more civic engagement. I don’t think that we should be celebrating anything that represents the brutalization of another culture.”

Keith, however, believes that the reinvention doesn’t need to happen on such a grand scale. “I think it can still be a reason for family to come together and eat food and be happy together,” he says. “It’s a good moral thing, but it shouldn’t be associated with the event in which we killed so many people, to take and keep the land we grew the crops on that we ate during the ‘great feast’. I think they should be fully separate, one is a horrific massacre that we shouldn’t celebrate, the other is just a day to be grateful and to be with family.”

Apr 19, 2019 | News |

By Audrey Carroll Contributing Writer

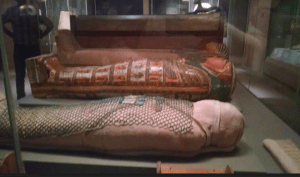

The museum not only focused on modern art– it also focused on ancient artifacts, too. (Photo by Emily Mokler)

Recently, Associate Professor of Art History and UMF Gallery Director Sarah Maline brought her Contemporary Art class, her World Film class and guests to the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston, MA. Entrance fees to the museum had been generously paid by a donor for Maine students and accompanying faculty.

Emma Pierce, a sophomore Visual Arts major and Graphic Design minor, felt as though the time flew by. “That museum is so big that you can get lost in it,” said Pierce.

Similarly, Emily Mokler, a senior Creative Writing major, and a guest on the trip was astounded by the vastness of the museum. “You could easily spend a couple of days in there, and still not see everything— it was that big,” said Mokler. “I feel like I saw maybe 10 percent of the place.”

Since the MFA is so large, it occupies artworks of all kinds. This ensures that any attendee is likely to find

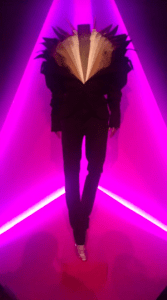

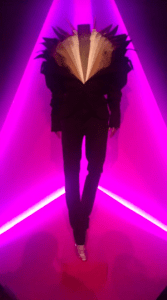

This designer look has broken the boundaries of gender through fashion. (Photo by Emma Pierce)

an exhibit or a specific piece of artwork that captivates them. For Mokler, this exhibit was that of the Egyptian mummies. “There was this climate controlled room, where they had different mummies from ancient Egypt,” said Mokler, “and they had hieroglyphs from the tombs. . .They structured these rooms so that you could see them laid out, and you could still see the colors— you know, some red and some blue.”

For Pierce, the piece that captivated her was “The Postman” by Vincent Van Gogh. “First of all, Van Gogh is my man,” said Pierce. What struck her about “The Postman” is how one can see the paint coming off of the original canvas. “Because he used a lot of paint… it gives it [the painting] texture, and it also shows where he put the brush— which is surreal,” said Pierce. “It’s almost like you were there with him.”

Pierce’s acknowledgement of the details of the artwork at the MFA, details that one can only witness in person, is exactly why Professor Maline takes this trip with her classes every semester. “The MFA offers us a chance to experience ‘live art,’” said Professor Maline via email, “The opportunity to experience live art— in your own physical presence— is so important. Very different from seeing it onscreen or projected. You see scale, texture and color in a different way.”

Though the trip is always a fun success, Professor Maline often experiences a moment of anxiousness during the outing. “We always have one student lost— either at the MFA at closing time or at Quincy Market after dinner— thank goodness for cell phones,” said Maline, “20 years ago when I first ran this trip we didn’t all have cells, so it was very stressful.”

Upon returning home from the MFA, Professor Maline’s students will complete a critical analysis paper of an artwork that they viewed on the trip. For this assignment, students “describe [an artwork] very closely, analyze it, then compare it to another artwork that is related conceptually— though not necessarily culturally or temporally,” said Maline.

Pierce is writing her analysis essay on a piece from the exhibit “A Gender Bending Fashion Show.” This exhibit displayed geometrically oriented neon lights surrounding outfits created by a variety of designers that “challenge the rigid definitions of dress based on gender,” said Pierce. This piece was designed by Viktor&Rolf for Tilda Swinton— an actress who “has a gender non-conforming style,” said Pierce.

This trip is a fun and educational experience for all, especially for the students in Professor Maline’s classes. “I recommend this trip to the patient and the open-minded,” said Pierce, “I would recommend it if you’re willing to experience art in the most open way— otherwise you won’t be able to enjoy it as much.”

Even for guests, exploring the MFA and Quincy Market was interesting and relevant. The excursion to Boston alone offered a different atmosphere for students to escape to. “This trip is great if you want to experience a change of pace,” said Mokler.

The trip to the MFA is taken once a semester. To attend, a student may either enroll in a class taught by Professor Maline or pay a $30 travel fee at the Student Life office on campus to attend as a guest.

Apr 19, 2019 | Opinion |

Avery Ryan Contributing Writer

The familiar ding of an Instagram notification jumped across my phone late on Sunday, March 31. Intrigued, I looked into the profile that had followed me. I wasn’t expecting the incredibly provocative artwork of UnBEARable UMF.

My first reactions were of intrigue and curiosity. The bravery of this artist to not only spray political graffiti on university buildings but to parade said graffiti on social media was astounding. The passion for spreading awareness that inspired this courage was successful; I immediately looked further into the Yemeni Civil War mentioned in the account’s first post. I also felt a strange reservation— should I follow this account? If I do, will somebody think I did the graffiti?

This fear emphasized what was so successful in a piece like this. Provocative public artwork lives on a wide spectrum of success, and this piece’s mystery solidified its accomplishment in starting conversation around its focal topics. This conversation was multiplied in the apparent shock that spread through campus in those first 24 hours. Calls to campus police, whispers among friends, and support and rejection of this approach surged across campus, leading to the premature climax of the exhibit: an email from Director of Public Safety, Brock Caton.

“Paw Prints Are Not Vandalism — The paw prints seen around campus are an on-going art project and do not need to be reported to Campus Police. For more information, please see the email traffic below.”

This short interjection into the project stands out as equally fantastic and disappointing. The confirmation of this being “an on-going art project” and not graffiti removed the assumed bravery of the artwork. It remained meaningful, yet lost much of its power. When I see the paw prints scattered across campus I no longer am driven to discover the motivation for such an installation. I no longer had that spark from the first 24 hours— the excitement and drive to understand why this person had been inspired to such bravery. This email violated my experience of the artistic merit of this project, as I’m sure it did for many others. By sending this email as quickly as they did, campus police prevented a number of students from that initial spark of curiosity that was present from Sunday night to Monday morning.

Was this a perspective that was unique to me? I sat down for a brief conversation with Student Senate Presidential candidate Jess Freeborn on the subject. “I didn’t see any of the paw prints until after the email was sent out. I think people were alarmed by them.” Freeborn said. “I think I would have been more curious if I had seen the artwork before the email.”

Nick St. Germain, a senior, echoed these sentiments. “[The paw prints] were pointed out to me specifically as an art project. I didn’t see a point to look further into it because it was just an art project. I would’ve been more excited if I’d seen it and thought it was graffiti.”

I couldn’t help but feel disappointed that both students were robbed of the excitement and curiosity of first seeing the artwork in its purest form. Their perspective had been modified and the artwork had been limited in its reach.

Was this the correct approach by campus police? As a university with an occasionally provocative arts program, more flexibility from campus police would have been incredibly beneficial. Imagine the conversations spread across campus had that email been sent out later— the historical and contemporary issues raised by UnBEARable UMF would have stood greater ground and the mystery of what would come next would have been an incredible excitement.