Apr 20, 2020 | Opinion |

Zion Hodgkin Assistant Editor

With the entire state and most of the world on full lockdown, most people know the fear of being forced to leave their house for any reason. Even a quick trip to the grocery store or the gas station can be anxiety-inducing and sometimes cause full week of stress, overanalyzing symptoms, and self-diagnosing, especially for those with an autoimmune disease like I have, having been diagnosed with diabetes type 1 in my early twenties. Despite this, last week I had to go into a clinic every week day, and have someone stick their hands directly into my mouth.

I had made an appointment over two months ago to get a tooth pulled. It was a lower molar, the furthest one back, and it had been causing me pain incrementally for about three months. We looked into having it filled, but the dentist said that it was too far gone, it would be safer at this point to just get it removed. They took an x-ray, and had me make an appointment with the Oral and Facial Surgery Clinic in Farmington. There was a pretty extensive waiting list and appointment was made for March 31st. As that date crept closer, the COVID-19 pandemic started to get worse, spreading rapidly across the world and closing businesses and schools across the country. A week before my scheduled visit, I still hadn’t heard anything from the clinic, so I decided to give them a call. I was met with an answering machine, freshly recorded, stating that the office was closed until further notice due to the pandemic. By this time, the pain in my mouth had become pretty terrible, and the thought of waiting weeks, or potentially months longer before I could do anything about it, sent me into a panic.

I called around to other dental clinics in the area, to see if there was anyone who could help me, and discovered that the Strong Area Dental Center, though not open to the general public, was still available to take people who needed emergency procedures. Luckily I fell into that category. I called on Thursday, April 2nd, and they were able to get me in later that same day. They took a look, noticed that there was some infection, pulled my tooth, and sent me home with a recommendation to take ibuprofen over the next week. The rest of that day and the day after went great. The pain had already lessened and I was incredibly grateful that I wouldn’t have to deal with the infection any longer.

Then the weekend started. I woke up in the most pain I’ve ever experienced in my entire life. It was worse than the time I had jumped face first into the water at Mill Pond Park and broke my nose, worse than the time I had three wisdom teeth shatter when I was getting them removed. There was immense pain at the extraction site, but on top of that, I could feel a throbbing in my entire face. My top row of teeth also were really painful, swollen, and incredibly sensitive to the touch.

I immediately called the dental clinic to see if I could speak to an on-call worker, but nobody answered, and the answering machine relayed the fact that they were closed for the weekend. The next two days were absolute misery. Turns out the extraction site had turned into a dry socket, which happens when the blood clot that builds up to allow for healing becomes dislodged.

On top of that, the oral trauma from the extraction had caused a horrific sinus infection, causing my sinus sacs to swell up, applying pressure to the top of my teeth and gums. I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t even watch TV because I was in so much pain. All I could do for 48 hours was stare at a wall in painful delirium, cry, and then stare at the wall again. I was begging the clock to tick faster, begging for sleep to pass some time, begging the sun to rise on Monday morning so I could call the dentist again.

On Monday morning, I called Strong Area Dental Center as soon as they opened and they allowed me to come in immediately so they could take a look. I pulled on some rubber gloves and headed out, barely able to see the road through the blinding pain. Once I got there and got in the chair, the dentist checked and saw that I did, in fact, have a dry socket. Unfortunately, it wasn’t going to be an easy fix. They were going to have to apply a numbing medicinal salve to the area for the next five days.

As the world became continuously more terrifying, and stopping to get gas spelled out a potential death sentence for my weakened immune system, I had to drive two towns over each day that week, to sit in a waiting room with other potentially ill people, and have a dentist stick his hands in my mouth every single day. Throughout this, I did my best to avoid contact with anyone besides my dentist (though I was afraid of him as well to a certain extent), but traveling and being in a clinic made that damn near impossible.

Now, a week after my last dentist appointment, my mouth is healing up nicely. My sinus infection on the other hand, has persisted, fluctuating from incredibly painful to relatively mild. All I’ve wanted to do is to finally stay at home, cut out the rest of the world and protect my weakened body. Instead, I’ve had to consider calling up the doctors to start the whole process over again.

Nov 21, 2019 | News |

Zion Hodgkin Contributing Writer

As Maine Gov. Janet Mills recently signed legislation replacing Columbus Day day with Indigenous People’s Day, perspectives on Thanksgiving are changing too. The ethics of the holiday’s very existence as well as the traditions in the celebration of it are now in question.

The first Thanksgiving was celebrated in 1621, and now, nearly 400 years later, it is celebrated in much the same manner. People get together with their loved ones, eat a ton of food, and feel happy about what they’ve achieved- but should we?

“The story goes,” writes one Business Insider article, “friendly local Native Americans swooped in to teach the struggling colonists how to survive in the New World. Then everyone got together to celebrate with a feast in 1621.”

However, the true beginning of Thanksgiving celebrations is believed to start instead in 1637, “owing to the fact Massachusetts colony governor John Winthrop declared a day of thanks-giving,” continues Business Insider, “to celebrate colonial soldiers who had just slaughtered 700 Pequot men, women, and children in what is now Mystic, Connecticut.”

Though the exact specificities and dates of this “First Thanksgiving” event may not be well known, most people, “are more aware that the story isn’t just what was taught in school,” proclaims Austin Kieth, former UMF student. “I just think people are more politically and historically involved. We are more aware of what Indigenous people went through.”

Katrazyna Randall, Associate Professor of Art, speaks about how she feels the holiday isn’t celebrated for the right reasons, but also why she thinks it isn’t celebrated in the right way. “One of the first things that strikes me, is how much it’s become about the idea of the nuclear family. In its origination it was about the harvest and about the community,” says Randall. “We don’t recognize ourselves as part of a community anymore, so that whole concept of it that is something worth celebrating doesn’t really exist anymore, it’s now about getting together with your family to have a dinner.”

Randall continues by thinking about how to shift the way a holiday born from a story of massacre is viewed and celebrated. “I sort of feel like things like Thanksgiving could go away, and that we need to invent new celebrations that celebrate our current civic reality,” Randall says. “I think that we should move more towards community celebrations and more civic engagement. I don’t think that we should be celebrating anything that represents the brutalization of another culture.”

Keith, however, believes that the reinvention doesn’t need to happen on such a grand scale. “I think it can still be a reason for family to come together and eat food and be happy together,” he says. “It’s a good moral thing, but it shouldn’t be associated with the event in which we killed so many people, to take and keep the land we grew the crops on that we ate during the ‘great feast’. I think they should be fully separate, one is a horrific massacre that we shouldn’t celebrate, the other is just a day to be grateful and to be with family.”

Nov 7, 2019 | Feature |

Zion Hodgkin Contributing Writer

Amidst the flashing strobe lights and roaring jams of the last two years, you could almost forget you were standing in a school cafeteria.

Every year, on the last Saturday before Halloween, UMF’s Association for Campus Entertainment (ACE) club transforms the Student Center into a spooky celebration. The Halloween dance has been one of the most anticipated annual events held at the school for the last few years. “A bunch of people show up,” said Madison Vigeant, one of the members of the ACE club putting the event together, “we usually have like 400 to 500 people every year.”

Sarah Szantyr, another member, chimed in saying, “And that includes students at the school, and also guests. I think we usually have about 100 to 150 guests each year.”

Inside the dance, it’s clear which of these students had been there before, as they immediately made their way to the front of the room, right before the stage, and started dancing, their costumes and accessories swinging around them.

“The dance has been going on for quite a long time,” Vigeant said, “at least five years, I would say, [but] probably ten.”

Szantyr nodded slightly. “It’s been going on since we’ve been here. This will be our third year putting it on.”

A student walked up to the table by the entrance to the dance, where Vigeant sat, and investigated the baskets brimming with items at the end of the table. “They’re the prizes for the costume contest,” Vigeant said with a kind smile. “We have a few different categories that you can enter for.” She leaned down, as if re-checking the contents of the baskets and continued, “We have scariest costume, a free one [where you can enter with any costume], funniest, couple, another couple, and most creative.”

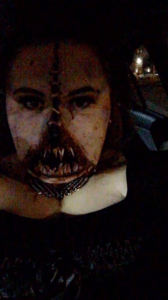

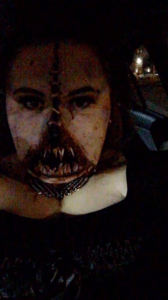

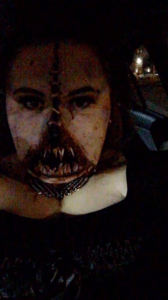

Alexis Ramee sporting her makeup, which won scariest costume. (Photo courtesy of Alexis Ramee)

Nodding excitedly, the student grabbed an entry form and began to fill it out.

“The costume contest has been happening for awhile too,” said Vigeant. “Last year was the first year we did it where I was involved. But if I were going to guess, the costume contest started a few years after the dance did. Maybe once the dance did well for a couple years.”

The costume contest has since become an iconic part of the Halloween dance, with most students signing up as they enter the event, and the night ending with the announcement winners. “We close the contest at midnight, and they stop the music for the announcement at 12:15 to 12:30,” Vigeant says, “and if the winner isn’t here, they’ll get an email, and can come pick up their prizes next week.”

Winner of scariest costume, junior visual arts major Alexis Ramee, left the dance before the winners were announced and woke up a week later to an email indicating that she won. “It made me really happy,” she said. “It made my morning.”

With a talent for special effects makeup and a preferred horror aesthetic, Ramee used liquid latex and polymorph plastic to create the illusion that her face had been split down a central seam and opening around her mouth. The look was meant to symbolize the importance of speaking a truth, even if it means tearing your mouth open to speak. “Generally I had pretty good reactions [to my costume], there were a couple of people that were slightly scared but I never, like, terrified anyone,” she said.

Even the campus police officers monitoring the entrance were taken aback by Ramee’s makeup. “Oh, they loved it,” Ramee said. “Even Brian Ufford was like, ‘Good makeup!’” While she said that she hadn’t seen anyone with makeup to compete with hers, she enjoyed the comedy of seeing two students dressed as bananas accompanying another dressed as a gorilla, as well as two Waldo’s. “It was just a really fun night to get away from all the school work.”

Darby Murnane in Medusa paint. (Photo courtesy of Darby Murnane)

As a dance full of partying college students naturally earns a reputation for crazy sights and stories, Szantyr and Vigeant reflect on what they’ve witnessed in years passed. “We don’t have any personal funny stories from the dances we’ve been around for,” Szantyr said, “but we were told on our first year of putting on the dance, that there would be a lot of people that were not fully aware of our surroundings,” she smiles a bit slyly and turns to look at Vigeant before continuing, “if you know what I mean.”

Vigeant shot back a smirk in response, as though she knew exactly what Szantyr meant, then added “Oh, also, one year an ACE member saw a girl beat up a pumpkin right outside of the dance.”

Oct 10, 2019 | News |

Zion Hodgkin Contributing Writer

English professor Sabine Klein sits in the small chair in the corner of her office, going over the information she’ll be discussing in her upcoming talk at UMF. “It’s about Norridgewock, well, specifically the horrific massacre of Native Americans that happened there. My talk is about the way that we sort of keep the memory of Norridgewock alive and why we do it.”

Klein will be giving her talk at the Emery Arts Center, on Oct. 23 at 11:45 a.m. It will be hosted by the New Commons Project, a group dedicated to looking at culture, both of the past and the present. Professor of English Kristen Case, the head of the New Commons Project, will be introducing Klein and discussing some of her accolades.

“She is a scholar of early American literature, her area of expertise is pre-colonial literature of the Americas,” Case says, “she really is an expert in this time period and in this region. Even though she’s an English professor here, her work is very historically informed. A lot of uncovering, and re-reading historical texts of all kinds, in order to be aware of more than one narrative about a specific moment in time.”

In learning about historical events, locally or on a global scale, it is generally difficult to escape a one-sided view of the events that transpired. It harkens to the age old saying, “History is always written by the winners.” Klein wants to simultaneously explore that concept when thinking about the local tragedy, and expand upon the awareness that students have of the event.

“What I realized is that we have this place of a massacre. . .but what’s even more interesting is the way that different communities have used the massacre to talk about the past,” she said.

“I’m going to talk about some of the monuments and literature that were affiliated with or written about that particular place in the 19th century. But, what’s interesting,” She grins a little to herself before adding “again, is that what happens in the 1820’s and 1830’s is that there’s an attempt to solidify American identity.”

“But the way that it’s being done is by basically writing about Indians, but writing about Indians as sort of the people, well” she pauses for a second, collecting her thoughts, “it’s the vanishing Indian trope. So this is the idea where people at the time were like ‘oh my god it’s so sad,’ and so you have this nostalgia of all the bad stuff that happened, but that nostalgia is a way of celebrating the new nation.”

Klein wants to explore how the memorialization of the massacre “serves Americans of English descent, versus Americans of French descent, versus Native Americans.” Each of the groups’ ancestral lines were directly involved in the massacre, and Klein will analyze how each of these groups of people are subsequently benefitting from the way the event is remembered, or not remembered.

Cali Turner, a student and an active member of the New Commons Project, is interested to see what the event has to offer, and wants to learn more about how people are affected by the different ways in which a story is told and remembered.

“I’m excited just to be able to further my education on the area I’m in,” Turner says, “I’m from Maine, but I’m not from Farmington, and it seems like especially with the other things we’ve been doing in New Commons, I think it’s important to be learning about the history, like the land and the people, and to be aware of some of the darker parts about it, because I didn’t even know that the Norridgewock Massacre was a thing.”

Turner also speculated about how historical events are remembered, and the way details are made available about those events. “I think our generation has gotten a bit better at being able to see all sides of an event,” she says, “I think for a long time people were only really able to learn by what they read from one history book, and now, because of how we were raised and because of our access to the internet, more recent generations have developed their own opinions.”

She continued, “We’ve gotten to the point now that most of us understand what’s okay and what isn’t. Or at least to where we can see multiple sides of an event, and know that what one source is saying, isn’t always the entire story.”

This semester, the New Commons Project is focusing specifically on Native history and issues in the state of Maine, and Klein’s talk will target an incredibly important and defining moment in Native history, very close to home.

Case thinks this event will be a “great opportunity for people who are interested in the history of this region, particularly the Native history of this region, to learn about one of the pivotal moments in that colonial time period. Learning about that history is vitally important in efforts to recognize the presence of the Abenaki in this region, not only then but also today.”

Oct 10, 2019 | News |

Zion Hodgkin Contributing Writer

Front St. in Farmington, recently remodeled, has had a longstanding reputation of being one of the least pleasant areas in an otherwise quaint college town. Though there are some wonderful businesses that reside there like Wicked Good Candy, Narrow Gauge Cinema, and Thai Smile, a good stretch of the road had been largely ignored for many years. The street lights were dim, and few and far between, the road has been documented to have some of the worst potholes in the state of Maine, and the Front Street Tavern, tucked away in the basement of a building, attributed to a sense of unease for many college students.

Moreover, one of the largest parking lots for students at UMF was located just past the tavern, down a small road whose entrance was almost completely pitch black at night. For students to access their vehicles, they had to walk directly past the entrance to the tavern on a dark street. Many felt unsafe, and most avoided any reason to access their vehicles at night.

Over the summer the area was remodeled and improvements include better sidewalks, more street lights and a repaved roadway.

One student, Leelannee Farrington, age 20 at the time, recalls why she decided she would never walk that street at night again. “I knew that pub was a bit seedy, so I always hurried past it.” She said “occasionally I would get whistled or hollered at, but because it was so dark I assumed it was just drunk guys being excited about anything that moved, I didn’t usually feel specifically targeted.”

The look on her face shifted a bit. “Then one night, there was a group of guys and one girl, standing at the end of the pub’s driveway under the light from like the only god damn street lamp on that whole road. They were smoking cigarettes and laughing about something as I walked towards their direction.”

Front Street, the new lights brightening up the newly-renovated street (Photo courtesy of Darby Murnane)

She paused before continuing a side note, “Actually I felt more at ease that time than I had some of the other times I’d walked past before, just because there was a whole group and a girl.” She said, “I always felt the most uncomfortable when it was just one or two guys catcalling at me, that’s when my anxiety about what could happen to me really started.”

Leelannee’s experience however, proved that even in groups there are people who will discard their inhibitions and attempt to harass individuals passing by. “One guy immediately noticed me,” she said, “and as I walked past the group he broke away from his friends and began following me, he was trying to flirt with me, and his words were all slurred and he stumbled a bit. I immediately felt panic as I was nearing an area of the road where the light didn’t reach.”

“I told him to fuck off,” she said, “and nothing bad came of it, but I wasn’t about to take that risk again.”

Richard Davis, the Farmington town manager of eighteen years, who was largely in charge of the planning process for the Front St. remodels, along with the Farmington Public Works Director, said he had “not heard about the harassment, but I can see where that might happen (unfortunately),” in an email interview. He also speculated that “the [Front Street] Tavern shutting down was an economic decision by the owners.” Regardless of the reasoning however, he believes that the closing of the Tavern as well as “the improvements [to the road] will help make people feel safer in that area of town, and while accessing their vehicles.